Africa, data and the yawning crocodile – a journey

Exploring the impact of digital technology on conflict dynamics and peace operations | Dr. Jakkie CilliersWorking with partners

As founder and executive director of the Institute for Security Studies from 1990 until stepping down in 2015 I have spent almost two decades working on peace and security issues in Africa, particularly with the Organization of African Unity that, in 2002, became the African Union. In this capacity and together with others, we partnered with the OAU/AU on the development of the Protocol on Peace and Security and a host of policies relating to peacekeeping including the conceptualization and establishment of the African Standby Force. From our offices in Addis Ababa and elsewhere the ISS continues to provide training and doctrine support to the African Union and a number of regional centres of training, much of it as part of the Training for Peace project funded by the Government of Norway.

Despite pressure to decrease and/or close down, peacekeeping remains hugely important in Africa. The deployment of a peace operation is the one sure tool that Africa and the international community has that, with sufficient resources and enough time, will steadily reduce conflict and build stability. Today Africa provides the majority of troops and police for such missions which is typically under African leadership.

My personal journey has also been shaped in quite a fundamental way by these experiences and the extent to which conflict and instability have waxed and waned in Africa. I have particularly come to embrace the importance of data – from a variety of sources and covering a range of basic markers of society and development – in enriching my understanding of the continent.

More peaceful, more prosperous

Data on conflict is, of course, incomplete and contested. But in studying conflict data and trends over time I believe that the various datasets are extremely useful in telling a broad story. These include that from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), the Social Conflict Analysis Database (SCAD), the Political Instability Task Force (PITF) and from the Center for Systemic Peace (CSP). All of them underline the relationship between prosperity and stability. Structurally, inclusive economic development coupled with substantive electoral accountability offers the best prospect for greater peace and stability. Generally countries become more peaceful as they become more prosperous and, above certain levels of income and development, democracy is the most stable form of government. Although, at low levels of development democracy may actually stimulate violence.

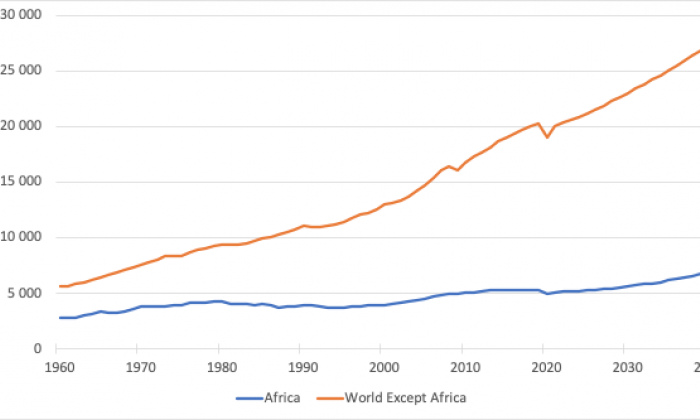

The problem is that although things are getting better in Africa, the continent is generally falling further and further behind global indices of wellbeing. Take, for example, GDP per capita which is a key if somewhat crude indicator of progress that reflects broad economic sophistication and the relative standard of living.

In 2019, GDP per capita in Africa is still only 26 percent of the average in the rest of the world and will remain at that level for the foreseeable future.

In 1960, generally considered the start of the post-colonial era, GDP per capita in Africa was about half of the average in the rest of the world and the gap has been growing ever since. It fell to below 40 percent in 1986 and below 30 percent in 2011. In fact, average GDP per capita actually declined by more than US$600 from 1980 to 1995. Then, from 1995 to the global financial crisis in 2008/09, Africa experienced its most sustained period of growth since 1960. But, in 2019, GDP per capita in Africa is still only 26 percent of the average in the rest of the world and will remain at that level for the foreseeable future. The situation in some countries, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zimbabwe has been nothing short of disastrous.

The associated figure presents this information in a line graph that compares the average GDP per capita in Africa with that in the rest of the world from 1960 and includes a forecast to 2040.

Like the jaws of a yawning crocodile, it paints a picture of increasing divergence and is a graph I often use to illustrate progress and challenges.

Figure: Africa vs Rest of the World: GDP per capita in purchasing power parity: from 1960 with a forecast to 2040

Source: International Futures (IFs) version 7.54 initialized from World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2018

The challenge of the growing divergence between Africa and the rest of the world is reflected in Africa’s marginal role in the global economy.

In 1960, Africa accounted for three percent of the global economy. Sixty years later that share remains unchanged despite the fact that Africa’s share of the global population almost doubled from 9 to 17 percent. Compare this to East Asia and the Pacific, a region that increased its share of global economic output from about 11 percent in 1960 to more than 30 percent today. East Asia’s share of the global population, on the other hand, has shrunk from 34 to 30 percent during this period pointing to its much more productive economies.

The same general storyline holds in relation to armed conflict. When total fatalities are adjusted for Africa’s rapid population growth, i.e. to represent the ratio of fatalities per million people in the population, it is clear that the fatality rate from armed conflict on the continent is slowly declining. Today Africans are significantly less exposed to organized violence than in the 1980s and 1990s and peacekeeping has been a huge contributor to this trend, even as new challenges such as the threat of terrorism and the impact of a pandemic such as COVID-19 intrude.

Changing the game

While things are improving in Africa, across almost all dimensions, progress is very slow.

Clearly something drastic is needed to change these rather dismal forecasts. Doing more of the same is not going to lead to tangible progress. The impact of COVID-19, the momentum from a burgeoning population, the continued growth of China, India and others, the swift pace of technological change and other disruptive events such as pandemics, presents a complex picture of challenges and opportunities that have to be overcome.

But what is clear is that on its current trajectory, Africa could be left further behind as development accelerates elsewhere. It is also evident that Africa will suffer immensely from the impact of changes in the global climate given its limited coping capacity. In fact it is very likely that Africa’s real development period, currently likely the second half of this century, will be curtailed by climate change across many dimensions. While no direct link between conflict and climate change has been proven, there can be no doubt about a destabilising effect on fragile security situations which may tip the balance away from fledgling stability, such as in Sudan.

These considerations led to a shift in my personal and professional research interests that included a stint at the Frederick S Pardee Centre for International Futures, University of Denver, using their long-term International Futures (IFs) forecasting platform. IFs is a global long-term forecasting tool that encompasses and integrates a range of development systems including demography, economy, education, health, agriculture, environment, energy, infrastructure, technology, and governance. It is like a massive algorithm with all the relationships carefully curated from academic literature. IFs has been designed and developed over several decades to form a series of relationships between systems and to generate its forecasts of where things are headed initializing from a huge amount of data. It allows the user to model what could be possible and what is required for such progress.

This type of analysis forces us to step back and appreciate the time required to transition from a war-economy to one characterized by peace and development.

In my view, this type of analysis is critical in the design of peace operations. It forces us to step back and appreciate the time required to transition from a war-economy to one characterized by peace and development. At the highest level, it could help to resist the intention to rush to elections and find an exit strategy when the fundamentals for stability and prosperity are not yet in place.

Upon my return from Denver, I established the African Futures and Innovation program at the ISS and we have, over several years, researched and published a set of detailed country and regional studies as well as a number of thematic studies on matters ranging from industrialization to governance and peace and security. Earlier this year I published a book, Africa First! that brought much of that work together in a single, accessible format.

Basically, what needs to happen for Africa to start closing the gap with global averages of wellbeing? And for the continent to become endogenously more stable, instead of relying on peacekeepers and others?

Of course if Africa could have talked itself into a higher level of development it would be doing very well. But only rarely do the many plans and visions translate into reality. Examples include the 1980 Lagos Plan of Action for the Economic Development of Africa, the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) and recently Agenda 2063.

The answer, it seems, is a series of fundamental transformations in the productive structures of African economies, ranging from demographics to trade integration. These transitions have all been modelled in Africa First! and in a current follow-on project, Potential2Prosperity, we are refining our forecast down to each individual African country using the African Union’s own Agenda 2063 ambition as lodestar. Starting in October 2020 we commenced with 15 expert sessions on Africa’s demographics, health, education, implementation of the continental free trade area, and so forth. In each sector we present a forecast of where we believe Africa is currently headed in that sector and the impact of an ambitious positive scenario to say industrialize or get more rapidly to its demographic dividend. Eventually we combine all of this in a single ambitious forecast where all good things go together to present a best case forecast of the true potential of Africa to prosper. We intend to present our draft outcome document in March 2021 for comment and input.

Among many other positive trends two stand out. The first is that modern technology offers huge opportunities such as in electricity generation and access, expansion of mobile broadband networks and better access to financial services that could, if harnessed, revolutionize education and doing business in Africa. The second is that Africa has the potential to benefit from a demographic dividend if it can succeed in reducing its current high fertility rates and invest in the health and education of its growing working age population. But eventually Africa has to also climb up the traditional developmental ladder that includes agricultural reform, industrialization and expanding its market (through trade integration, amongst others).

The human factor

In the modelling that my team has been doing, we sometimes refer to this as the ‘standard model of development’. It cannot promise progress since we cannot model human agency and clearly leadership matters. Few, for example, could have foreseen the 2020 situation in Ethiopia, now under threat of civil war as the central government of Prime Minister Abiy confronts the efforts at greater autonomy from its Tigray region. Until very recently Ethiopia was the most rapidly growing economy globally and had been for a decade. That promise, indeed progress in the entire Horn, is under threat.

Even so, progress is slow and international support for peace operations in Africa appears to be waning. If peace operations take on board more fully the potential of data and analysis on the big lines of development to show their own impact, they have a chance to showcase the vital role they play in promoting stability – and thereby prosperity – on the African continent.

More information about Africa First! and other publications is available at www.jakkiecilliers.org

Download article

IMAGES

- Author | Jackie Cilliers priv.

- Binary code globe | Pixabay, Gerd Altmann