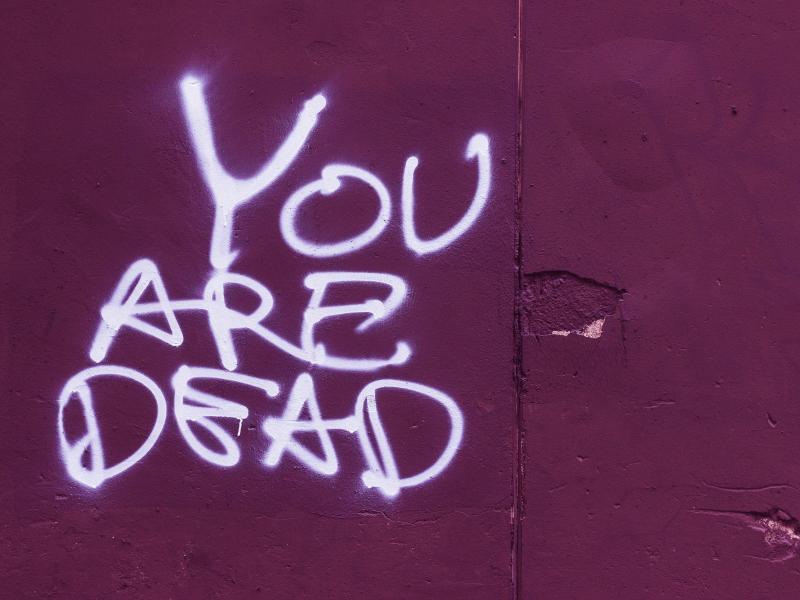

Hate speech - poison for mandate implementation

Supporting the implementation of mandated tasks through digital technologies | Monika BenklerIn 2019, UN Secretary-General António Guterres described hate speech as "poison" and a "global danger”. Hate speech impacts international peace operations by undermining mandate implementation, in particular political processes, and tarnishing a mission’s credibility. The "tsunami of hate" that the UN observed in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic once again raised awareness about the digital spread of harmful information and the need for effective countermeasures. Based on his Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech (May 2019), Guterres published more Detailed Guidance on Implementation for United Nations Field Presences in September 2020. A central role in implementing key commitments to address hate speech falls to digital technologies.

Hate speech in the context of peace operations: the status quo

It is difficult to overestimate the damaging effect of hate speech. It not only restricts people in the exercise of their fundamental and human rights and increases tensions and conflicts between groups, but can also prepare the ground for physical attacks against members of the respective groups. The atrocities against the Rohingya in Myanmar in 2017, for example, were in large part the result of hate speech and incitement to violence on the internet. Hate speech is context-specific and – even if it is a separate phenomenon – is often closely linked to disinformation, i.e. information that is false and deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organization or country (see also Disinformation-Amplified Hate Speech). In several countries where peace missions are deployed, the phenomenon is well documented, such as in South Sudan or Libya (see PeaceTech Lab's Hate Speech Lexicons).

Regulations of online communication not only lead to the defence but also to the restriction of the right to freedom of expression.

States are increasingly creating legal frameworks to combat hate speech and assigning responsibilities to social media platforms. In practice, however, regulations of online communication not only lead to the defence but also to the restriction of the right to freedom of expression. In fact, 155 internet shutdowns were documented in 29 countries in 2020 – including in four countries with peace operations. In 19 of these cases the official reason was to combat the spread of hate speech (Internet Shutdown Report, Digital Rights Landscape Report).

To some extent, hate speech has found its way into the mandates of UN peace operations. Missions with a Protection of Civilians (POC) mandate are generally tasked with countering the spread of hate speech with information and strategic communication as part of their "protection through dialogue and engagement" activities (UN POC Policy). Some operations also have an explicit mandate related to hate speech, including UNMISS in South Sudan (Res. 2459/2019) and MINUSCA in the Central African Republic (Res. 2499/2019). MINUSCA's human rights component, for example, monitors hate speech on social media and works with Facebook to remove harmful content. Another example is UNSMIL, the Special Political Mission in Libya, where problematic messages on social media have deepened rifts between communities. UNSMIL's human rights component has sought innovative approaches by working with Libyan journalists and Facebook to develop a common understanding of hate speech and strengthen responsible journalism (see OHCHR, 10/2020).

The UN's new strategy: 13 key commitments

With his UN-wide Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech, Secretary-General Guterres aimed to intensify and structure the organisation's efforts. On the one hand, the goal is to address root causes and drivers of hate speech, and on the other, to enable effective UN responses to the impact of hate speech on societies. The 13 key commmitments (see box) frame hate speech as a complex societal problem, that requires engagement with different stakeholders and a range of approaches such as monitoring and analysis, communications, education and advocacy, as well as access to justice and victims’ support. This provides a variety of entry points for UN peace operations for supporting the implementation of these commitments.

The 13 Key Commitments of the Strategy

1 Monitoring and analyzing hate speech

2 Addressing root causes, drivers and actors of hate speech

3 Engaging and supporting the victims of hate speech

4 Convening relevant actors

5 Engaging with new and traditional media

6 Using technology

7 Using education as a tool for addressing and countering hate speech

8 Fostering peaceful, inclusive and just societies to address the root causes and drivers of hate speech

9 Engaging in advocacy

10 Developing guidance for external communication

11 Leveraging partnerships

12 Building the skills of UN staff

13 Supporting Member States

Source: United Nations Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech, May 2019

Guterres' clarification of terms

A major problem in the regulation of hate speech is the absence of a universally accepted definition under international law. There is a precursor in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966, Article 20, paragraph 2), according to which states must prohibit by law "any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence". Central to the definition is the issue of group-based misanthropy. Similarly, the UN Secretary-General prefaces his strategy with the following understanding:

"Any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other identity factor. This is often rooted in, and generates intolerance and hatred and, in certain contexts, can be demeaning and divisive.”

Implementation of the strategy

The SG's Detailed Guidance on Implementation for United Nations Field Presences acknowledges the various facets of hate speech and provides peace operations with a "menu" of options to be prioritised according to the context and mandate, translated into country-specific action plans and implemented together with state and non-state actors. All in all, 107 individual measures seek to operationalise the 13 fields of action of the strategy and action plan.

To classify the severity of hate speech (top, intermediate and bottom level), peace operations should apply the six criteria of the Rabat Threshold Test (2012). In the case of “top level” hate speech, this entails promptly alerting the relevant social media platform and recommending concrete actions (Commitment 6) as well as encouraging an independent and impartial investigation and supporting strategic litigation (Commitment 3). Direct intervention options are also available in the context of strategic communication (Commitment 10). Online channels have opened up various possibilities for peace operations to quickly distribute messages to a broad audience.

Use of new technologies

In various places in the field-level guidance, the Secretary-General recommends that peace operations employ new technologies in their efforts to address hate speech, especially in monitoring and analysis (Commitment 1). As part of the analysis, understanding content (message), actors and their motivation (messenger) as well as the distribution channels of harmful information (messaging) are key to assessing their influence on the conflict environment and defining appropriate countermeasures.

Artificial intelligence (AI) technologies for automated text analysis can support peace operations in this regard. The difference between manual assessment and an automated social media analysis is the ability to analyse thousands of comments and users and quantify their reactions, topics of conversations, sentiments, etc. (see also Take back the analysis: Five things you can actually learn about a conflict context from social media on this blog). Carefully adapting the system to the environment is important, as the potential bias of AI-generated analysis is a significant challenge (A/HRC/44/57).

Peace operations can use a number of tools developed in house, including applications tested by the UN Global Pulse initiative in recent years, such as the Qatalog, or the pioneering Radio Mining Hate Speech in MINUSMA. However, these are not yet being used systematically across peacekeeping and special political missions.

Other important entry points in the digital space is the governance of harmful content (moderation, oversight and regulation) and the promotion of initiatives that use online counter-speech to minimise the harmful effect of hate speech and to change the culture of debate as a whole (Commitment 2).

For preventive action by peace operations, the ability to efficiently evaluate the large volume of information on the web and to incorporate trends into conflict analysis is crucial.

Challenges

Addressing hate speech is a complex endeavour and requires action at different levels by different actors. The Secretary-General has formulated very concrete recommendations, which can form a solid basis for developing country-specific action plans. Drawing on the commitments and the detailed guidance, in practice, each context will require missions to design their own context-specific approach, using relevant tools, engaging key stakeholders and recognising the political dynamics.

Cooperation with partners from the tech industry, especially in monitoring hate speech, is an important building block. The need for a strategic approach to this relationship that duly considers the intricacies and risks involved, is underlined by the SG’s proposal to establish an inter-agency task force with a particular position (“contact point”) to serve as key interlocutor between the UN field presence and Internet companies.

For preventive action by peace operations, the ability to efficiently evaluate the large volume of information on the web and to incorporate trends into conflict analysis is crucial. New technologies should be used systematically here, but must always be accompanied by the "human" element – the analytical capacities und the understanding of a dynamic conflict environment to place the results in context.

DOWNLOAD ARTICLE

IMAGES

- Author | Monika Benkler priv.

- Image "Hate" | Pixabay, Gerd Altmann

- Image "You are dead" | Unsplash, Crawford Jolly