Post-pandemic peace operations

Exploring the impact of digital technology on conflict dynamics and peace operations | Sanjana HattotuwaCoronavirus is a wicked problem, to use American philosopher and system scientist C. West Churchman’s term from 1967, referring not to evil but a multi-variate problem-space that resists resolution, and further, becomes more complex the more attempts are made at solving it. Arguably, so were peace operations before the pandemic. But what Coronavirus has done – although not everyone realises it and there is significant variance in how prepared institutions are – is to render even more complex and interwoven the conflict landscape in a peace operations theatre.

The interdependencies of information and communications technologies (ICTs) in all forms of peacebuilding and peace operations pre-date the pandemic. As much as violence and its generation are enabled by digital platforms, including social media, these platforms also contribute to and help in conflict transformation, including the mitigation of hate, toxicity and violence. In the long-shadow of Coronavirus – especially in existing geographic theatres of peace operations – ICTs will be, in both old and entirely new ways, inextricably entwined in how conflict dynamics will seed and spread as well as in how peace operations deploy and respond. In this short article, I delve into both the overarching context of application, as well as six specific ideas for innovative roll-out of ICTs in peace operations, post-pandemic.

We need to plan how we are going to live in a future that hardly bears thinking about. We need brains. And we need heart. And we need accountability. Enough of the cheap, stupid theatrics. (Scroll.in)

New drivers of instability

The pandemic impacts everyone, but not everyone is impacted equally. Peace operations will also deal with the fallout of Coronavirus collectively, though to varying degrees of operational complexity. Entire geographies will need to be remapped on account of new drivers of instability and a systemic fragility that teeters on the verge of complete collapse. States, weakened by protracted violent conflict or complex political emergencies, now face added challenges to institutional frameworks that are weak and unable to deliver essential services. New elites will emerge, who will use health indicators, access to healthcare infrastructure and medicine and, eventually, immunity as a new currency to broker deals and power. This new post-pandemic elite will create new socio-political, economic, communal and religious division, anchored to identity, gender, geography, health, mobility, access to services and economic production.

Epidemiological tracing will produce data that will be commodified. With this commodification will also come counterfeit, allowing the purchase of records and identities to pass through, or gain access into areas – both local and international – that symptomatic or asymptomatic carriers of the virus will be, with good reason, barred from. The resulting stochastic spikes in infections will result in socio-political and economic instability that could lead to entire areas – already impoverished, or newly discovered as community transmission hotspots – to be sealed off, adding to morbidity and mortality. Violent othering and xenophobia – seeing those ‘not from or one of us’ as the carriers of Covid-19 – will lead to armed ghettoization of neighbourhoods, communities, and geographic areas.

A changed world for peace operations

Peace operations that had mapped the topographies of violent conflict will need to embrace new drivers of instability from aspects of society and polity they may never have dealt with in a sustained and systemic manner – including, but not limited to the provisioning of and access to healthcare, clean water, disinfectant, soap and sanitation. The most mundane things – like lining up for bread, accepting cash, using a toilet, sharing a meal, going for prayer, mourning the dead, celebrating a birth, attending a wedding, caring for the elderly – will carry the greatest risk in societies already rent asunder by poverty and violence. Peace operations will have to plan for the rapid escalation in violence that is the consequence of virus vectors that have not been accounted for. Through negligence, ignorance, opportunism or malevolence, the pandemic will spread as quickly as it can, to the greatest degree it can. Peace operations at present are not geared to respond to this level of indiscriminate infliction amongst the populations they work with.

Austerity can be used to innovate, reskill and retool.

A systemic response

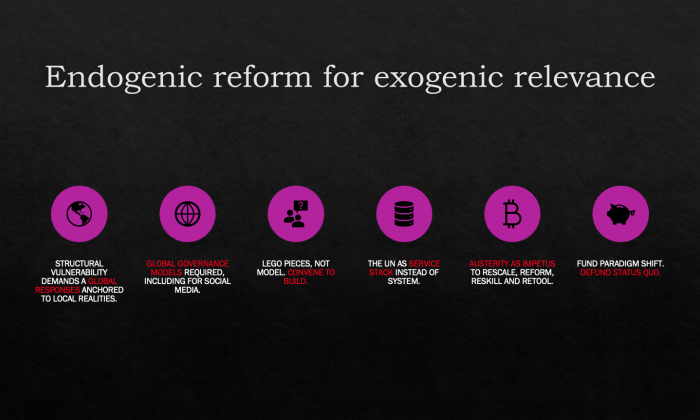

In a recent presentation to the UN Departments of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA) and Peace Operations (DPO), I explored six pillars the UN’s systemic response to the pandemic could be anchored to, including peace operations.

- The pandemic’s upheaval is global, but is felt at home, locally. It makes little sense to someone without a job, and going hungry, to know or be told that global supply chains and oil prices are in historically uncharted terrain. And yet, local problems cannot be addressed by hiding behind sovereignty. No state can overcome Coronavirus alone, and every state is at risk of the pandemic for as long as even one cannot eradicate it. Ironically, climate change features precisely the same set of challenges, but unlike the pandemic, does not enter lives or the public imagination as an immediate existential threat. Given the global nature of the problem, the solutions required are by definition, international. But not unlike WHO’s guidelines, the application of templates designed to tackle a pandemic globally, require grounded, contextual knowledge and awareness to adopt and adapt.

- Called an ‘infodemic’ because of the sheer volume of disinformation around the pandemic, Coronavirus has parked for the moment discussions around the regulation of social media companies in the US and other jurisdictions. These conversations need to be rekindled, albeit with care and caution around states that will use the pandemic as an excuse to legislate against inconvenient truths from being produced and engaged with by enraged populations. Social media regulation is needed for quality assurance of content, ensuring near-ubiquitous platforms and products that are now the DNA of social, political, cultural, and economic interactions, reject all forms of violence, hate, harm and toxicity.

- Peace operations and the UN need to be modular in their approaches, which is a combination of lean innovation in austere contexts as well as breaking up aspects of what until recently were part of a larger whole. From large, top-heavy institutional or command and control structures to more responsive, agile, iterative management and deployment, the pandemic requires efficient, effective and sustainable solutions that are locally owned, driven and sourced. This flips the model of peace operations as structures that are imposed from outside, to mandates and missions that are smaller and can swarm to meet surge demands.

- Inspired by computer programming models, peace operations solutions can be mixed and matched from a central repository to best fit local challenges. These architectures can be created to extend to the field, so that entering the contours of a problem will result in the display of or access to potential solutions, along with of course localisation. The consolidation of learning and experience, tools and resources, platforms and apps, services and products, can help in the discoverability of applications that may negate the need to recreate them from scratch, in order to meet a specific need.

- Given the budget cuts and cash crunch systemwide at the UN, and across all commercial and state enterprises across the world – itself an unprecedented event – austerity can be used to innovate, reskill and retool. A few months ago, video calls were the last resort or only used in emergencies. Now they are the default mode of communication for all things, always, with everyone. Twitter as a company is making Work from Home (WFH) something that will stay even after the pandemic fades away. As companies and other public, private entities discover that business continuity can be maintained by staff not reporting physically to offices, workflows, mobility, access, bearing witness, monitoring, responding, deploying and so much more will change in the months and years ahead. Peace operations will always need troops on the ground, but support staff, and exact numbers, will change, without necessarily impacting mission effectiveness and mandate implementation.

- Finally, the UN and peace operations can choose to actively use the pandemic to jettison old thinking. Institutionally incapable of rapid reform, the pandemic asks the UN – and similar institutions – to change or perish. There is no middle ground because the virus doesn’t care. It will seed and spread until a vaccination is found, and even then, leave a lasting mark on a world that will take years, if not decades, to recover.

Even a pandemic will not automatically bring about lasting change unless there is agitation for it from within institutions.

Seizing the opportunity for change

“We know what we are, but know not what we may be” – in Hamlet, Shakespeare asks us to think about what more we can be, beyond what is known. It asks of us a simple question – what is the world after Coronavirus that we seek to inhabit? When so many talk about returning to normal life – invisible yet inherent in that statement, and often through no fault of the person who desires it – is a systemic violence. Inequity and inequality, the evisceration of public services including health for decades, the over-reliance on fragile supply chains, the growth of unsustainable products and services, the hidden labour that fuels commerce and industry, the poverty of governments and the paucity of planning – all these are more of what the ‘normal’ 2020 began with. Do we go back to that? Do we go back to peace operations design and deployment as it once was? Will the UN, states, private and public institutions revert to type?

I risk disappointment to hope this isn’t the case, but strongly argue that even a pandemic will not automatically bring about lasting change unless there is agitation for it from within institutions, as well as the general public. Herein lies the rub. Institutions are extremely capable of perpetuating the problems they were setup to address. Business continuity is not about innovation or reform – it is about carrying on as one always did, with a minimum of disruption. But deviation from the normal – brought about by Coronavirus – must result in lasting innovation, and institutional responses, that do not return to what exacerbated the spread and impact of the virus. The virus is in this light the perfect change-agent, with no patience around arguments against why something cannot be done, and instead strengthening voices, until recently at the margins, who articulate a vision for community, country, region and world as a better, more just and peaceful place.

Download article

Images

- Author | Sanjana Hattotuwa priv.

- Endogenic reform | Sanjana Hattotuwa