Unlocking the futurist mindset – strategic foresight for peace operations

Partnering for digital technology innovation | Mallika AuplishThe term peace operations conjures up images of robust military and police personnel navigating the murky and often violent path from conflict to peace. The passage of (literal and necessary) day-to-day ‘firefighting’ associated with peace operations lends itself to a scenario where thinking and planning for the future seems difficult if not entirely impossible. How do you build a resilient future when the present is abstruse?

What strategic foresight isn’t (and is)

Strategic foresight – also referred to as futures work, futures studies, futurism, and foresight – is an umbrella term that presents a range of practical organizational activities to inform decision-making and reach desired outcomes. The premise of foresight comprises building the future as one chooses to. The process is not about providing accurate forecasts but is about reducing the ambiguity of the future by blending an array of existing research and analysis methodologies to curate strategy.

Foresight has been used by the private sector to guide decisions and explore new pathways; by governments and research institutes to counter emergent or discontinuous trends; by international organizations like the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and UNDP to support long-term planning and transformational change in developing countries; and in NATO’s military and defense planning to visualize the future security environment. Compared to more traditional models of planning that tend to focus on current issues or those from the recent past, foresight can help meet challenges posed by emerging environmental threats and political and demographic shifts while harnessing the opportunities catapulted by emerging technologies and innovations. Through its systems approach, incorporating foresight into traditional planning can help ensure that short- and medium-term operational planning not only aligns with but also complements long-term strategic transformations. In preparing for a future that is ambiguous, complex and rapidly changing, strategic foresight can help peace operations both address immediate conflict and build long-term peace.

Foresight can help meet challenges posed by emerging environmental threats and political and demographic shifts while harnessing the opportunities catapulted by emerging technologies and innovations.

Future-proofing peacekeeping

The evolution of peacekeeping from specific targeted operations (e.g. for ceasefire or based on a peace agreement) to more arbitrary dynamic concepts (e.g. transition, enlargement and integration) has significantly changed how conflict resolution is evaluated. Resource austerity coupled with the shift from inter-state to intra-state tensions has ensured that a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to peacekeeping is not effective. Facing a broadened mandate juxtaposed with limited resources amid mounting political pressure, UN peace operations face the arduous task of tackling new forms of global geopolitical tensions requiring targeted, localized responses. Through the vast scope and concomitant ways in which its methodologies can be customized and scaled as required, strategic foresight can help peace operations with cost optimization, response-time reduction and effective resource allocation.

Historically, foresight has played a key role in military and defense planning, with scenario planning and war gaming utilized as strategic foresight methods. The sole use of these methods however has limitations in that they do not consider the likelihood of multiple alternative futures. Ignoring the (possible) occurrence of black swans, anomalies or outliers leaves organizations and firms vulnerable to disruptive or detrimental events. Peace operations provide a unique opportunity for foresight methodologies to be utilized to help avoid undesirable end states by planning for future possibilities beyond the horizon.

Although a wide range of foresight methods exists, some may be especially relevant to peacekeeping given their high applicability to so-called “VUCA” environments i.e. those characterized by Volatility, Unpredictability, Complexity and Ambiguity. Using strategic foresight can help avoid myopic actions that may not meet the longer-term challenges of non-linear changes or radical systemic disruptions, as are emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic. These will likely have created long-term ruptures in the economic development, health gains and social fabric of countries with rampant conflict.

Frameworks in action

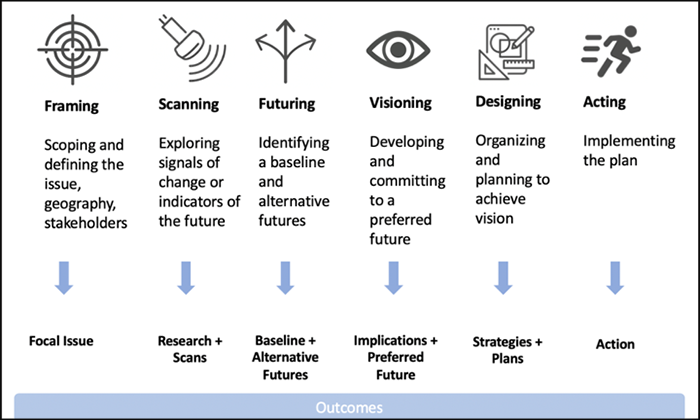

Framework foresight provides a practical, structured approach for forecasting and planning.

This comprehensive model can help make sense of complex systems, overlapping trends and intersectional drivers of change – a tool to help address the challenge of increasingly wide-ranging responsibilities faced by UN peace operations. Caution must be taken to ensure that the ‘actioning’ stage is not limited to a checkbox but is linked to existing mechanisms to circumvent redundancies.

McKinsey's Three Horizons allows for the maintenance of current growth while planning for future change. This model provides a framework that can enable senior management to conceive what an ambidextrous organization may look like – executing existing business models while simultaneously enabling innovative capabilities – thereby extinguishing the apparent paradox of productivity vis-à-vis innovation. Its time-based approach may be applicable to peacekeeping environments where radical change is practically difficult and/or has not historically been associated with positive change. Incorporating ambidexterity into peace operations can facilitate a robust, streamlined and cost-effective approach towards innovation.

The Causal Layered Analysis (CLA) provides a collaborative approach that acknowledges the role of diverse worldviews and myths contributing to a situation and provides room for dialogue on culture change. It helps identify multiple levels of change to inform a coherent view of the future. By recognizing social causes and systems – including economic, cultural, political and historical factors – in addition to the role of metaphors and myths in forming culture and ensuing narratives, CLA builds upon quantitative data in identifying drivers of change. In the absence of more conventional forms of evidence-based data gathering, community-driven narratives can be a powerful source to identify interventions for country support.

Challenges and recommendations

The application of technology within the distinct environment of peace operations presents a unique set of challenges and questions. For instance, from an operationalization standpoint: how do you implement digital solutions without basic telecommunications infrastructure? Or, in terms of ethics: how critical is data privacy when basic physiological and safety needs are not met? Or, in terms of resource allocation or triage: whom should digital access be prioritized for – governments (maintenance of rule of law), vulnerable populations (a social welfare perspective) or the youth and/or working population (for economic progress)? Or, from a legal standpoint: should (and if so, how) we regulate content vis-à-vis free speech especially in conditions where trust in governments is reduced/non-existent?

Although scientific and technological advances have reaped great benefits for development, their use also raises several ethical, legal, social and security concerns. Perhaps one of the most critical challenges and paradoxes in building peace operations’ tech strategy today is the need to build a culture of innovation and foresight while combatting a firefighting mindset. Herein lies the paradox of building a culture honoring failure – a key tenet of innovation culture – when the cost of failure in a conflict environment could be grave. Budget austerity and insecurity, and its impact on resource allocation in ensuring the immediacy of needs met, poses another challenge in anticipating over-the-horizon needs.

Herein lies the paradox of building a culture honoring failure – a key tenet of innovation culture – when the cost of failure in a conflict environment could be grave.

One limitation of foresight that can easily turn into a weakness is a lack of understanding of its functionalities. Thus, it is imperative to first understand that foresight is an enhancement of planning methods via explicitly exploring VUCA realities, alternative futures, and by asking people to forsake existing cognitive and behavioral biases. Many foresight actions also suffer from a lack of follow-up or implementation. Even if intended and foreseen, limited funding and rigid structures may hinder innovation and flexibility in ways of working. A potential solution – as also embraced by several governments like Singapore and the UK – is to embed strategic foresight into existing planning structures.

The use of innovative methods is paramount in moving towards institutionalized innovation and continuous technological adaptation, particularly within an organization as vastly complex as the UN. An innovative culture, by definition, calls for the need for flexible and agile ways of working. Strategic foresight offers a pragmatic way to balance wide-ranging mandates while identifying opportunities for technological and innovative solutions without reinventing the wheel. Instead, it also offers fluidity to refine effective methodologies and, more critically, put existing frameworks into practice.

(Re)building the future

The 2015 TIP report cited the need to “anticipate and manage the effects and consequences of added range, reach, volume and impact” in deploying and using technology. In its 256th meeting, the Special Committee on Peacekeeping Operations cited the need for peacekeeping to adopt a “more flexible posture, tailored to specific conflicts and endowed with the resources and capabilities needed to improve foresight in tackling new threats”.

As a trendspotting tool, strategic foresight can be useful in looking at short-, mid-, as well as long-range futures. It can help determine how best to invest available resources to realize desirable futures and avoid less desirable outcomes while integrating the diversity of cultural contexts. If the UN can incorporate strategic foresight, futures-thinking and horizon-scanning into its strategic planning framework, Member States can also be better supported in anticipating and preparing for, rather than simply responding to, conflict resolution and peacekeeping needs.

The pandemic has unearthed an unprecedented wave of changes to the way we live. Marred by uncertainty and unpredictability, acute events like these have magnified the need to be prepared for the seemingly implausible. Changing social contracts present a tabula rasa with an opportunity to rewrite the way things have been done. The disruptive forces of COVID-19 have (forcefully) opened a window for us to pause, reflect and calibrate innovations – and to (re)build organizations, societies and mindsets into levers of change that can transform uncertainties into opportunities.

Download Article

Images

- Author | Mallika Auplish priv.

- Framework Foresight | Source: Exploring Futures the Houston Way, Andy Hines and Peter C. Bishop, Futures, 51 (2013) 31–49.

- Scanning, Visioning, Action (Teaser) | Mallika Auplish